The Yanomami

.

The Yanomami, also spelled Yąnomamö or Yanomama, are a group of approximately 20,000 indigenous people who live in some 200–250 villages in the Amazon rainforest on the border between Venezuela and Brazil.

live in villages usually consisting of their children and extended families.

The Yanomami are known as hunters, fishers, and horticulturists. The women cultivate plantains and cassava in gardens as their main crops. Men do the heavy work of clearing areas of forest for the gardens. Another food source for the Yanomami is grubs.[1] Often the Yanomami will cut down palms in order to facilitate the growth of grubs. The traditional Yanomami diet is very low in salt. Their blood pressure is characteristically among the lowest of any demographic group.[2] For this reason, the Yanomami have been the subject of studies seeking to link hypertension to sodium consumption.

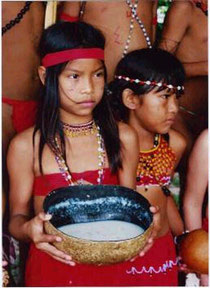

Rituals are a very important part of Yanomami culture. The Yanomami celebrate a good harvest with a big feast to which nearby villages are invited. The Yanomami village members gather huge amounts of food, which helps to maintain good relations with their neighbors. They also decorate their bodies with feathers and flowers. During the feast, the Yanomami eat a lot, and the women dance and sing late into the night

The Yanomami live in villages usually consisting of their children and extended families. Village sizes vary, but usually contain between 50 and 400 people. In this largely communal system, the entire village lives under a common roof called the shabono. Shabonos have a characteristic oval shape, with open grounds in the center measuring an average of 100 yards (91 m). The shabono shelter constitutes the perimeter of the village, if it has not been fortified with palisades.

WARAO PEOPLE

The Warao are an indigenous people inhabiting northeastern Venezuela and western Guyana. Alternate common spellings of Warao are Waroa, Guarauno, Guarao, and Warrau. The term Warao translates as "the boat people," after the Warao's lifelong and intimate connection to the water. Most of the approximately 20,000 Warao inhabit Venezuela's Orinoco Delta region, with smaller numbers in neighboring Guyana and Suriname. They speak an agglutinative language, also called Warao.

On the wide Orinoco River and its fertile delta composed of islands and marshes, Warao people inhabit wall-less thatched-roof huts built upon stilts for protection against floods. These houses are usually built on the highest ground to avoid the annual floods. Sometimes a group of houses is built upon a single large platform of trees. The huts each possess a clay cooking pit or oven located in the center, with sleeping hammocks encircling it. Besides the hammocks, the only other furniture sometimes present are wooden stools, sometimes carved in[edit] Transportation

Warao use canoes as their main form of transportation. Other modes, such as walking, are hampered by the hundreds of streams, rivulets, marshes, and high waters created by the Orinoco. Warao babies, toddlers, and small children are famed for their ability to hold tight to their mothers' necks, as well as to paddle. They often learn to swim before they learn to walk.

The Warao use two types of canoes. Bongos, which carry up to 50 people, are built in an arduous process that starts with the search for large trees. When an old bongo is no longer usable, a consensus is reached by the male leaders of each household on which tree is best.

At the start of the dry season, they find the tree and kill it. At the end of the dry season, they return to cut it down. It is then hollowed out and flattened with stone tools traded from the mountains (or local shell tools) along with fire.

The other type of canoe is a small, seating only three people, and is used for daily travel to and from food sources.

WAYUU PEOPLE

Wayuu (also Wayu, Wayúu, Guajiro, Wahiro) is an Amerindian ethnic group of the La Guajira Peninsula in northern Colombia and northwest Venezuela.

The Wayuu language is part of the Maipurean (Arawak) language family.

A traditional Wayuu settlement is made up of five or six houses that made up caserios or rancherias. Each rancheria has a name after a plant, animal or geographic place. A territory that contains many rancherias is named after the mother's last name, because of the matriarchal structure of the Wayuu culture. The Wayuus never group into towns and rancherias are usually isolated and far from each other, to control and prevent mixing of their goat herds.

DISCOVER ONE OF A KIND ART WAYUU https://www.myputchi.com/collections/all

The panares

Panare is a Cariban language, spoken by approximately 3,000–4,000 people in Bolivar State in southern Venezuela. Their main area is South of the town of Caicara del Orinoco, south of the Orinoco River. There are several subdialects of the language. The autonym for this language and people is eñapa, which has various senses depending on context, including 'people', 'indigenous-people', and 'Panare-people'. It is unusual in having object–verb–agent as one of its main word orders, the other being the more common agent–verb–object. It also displays the typologically "uncommon" property of an ergative–absolutive alignment in the present and a nominative–accusative alignment in the past

Ye'kuana people

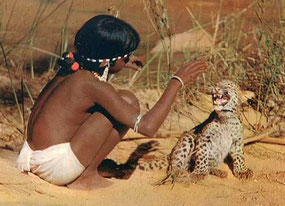

The Ye'kuana, also called Ye'kwana, Ye'Kuana, Yekuana, Yequana, Yecuana, Dekuana, Maquiritare, Makiritare, So'to or Maiongong, are a Cariban-speaking tropical rain forest tribe who live in the Caura River and Orinoco River regions of Venezuela in Bolivar State and Amazonas State. In Brazil, they inhabit the northeast of Roraima State. In Venezuela, the Ye'kuana live alongside the Sanumá.

The first reference to the Ye'kuana was in 1744 by a Jesuit priest called Manuel Román.

There are some 6,250 Ye'kuana in Venezuela, according to the 2001 census, with some 430 in Brazil.

Jean Liedloff came into contact with the Ye'kuana during a diamond hunting trip. She based her book The Continuum Concept: In Search of Happiness Lost on their way of life, particularly the upbringing of their children. The infants are normally in 'skin contact' 24 hours a day with their mother or with other women who take care of them[3]

Pemon People

The Pemon (Pemong) are an indigenous people of South America, living in areas of Venezuela, Brazil and Guyana.[2] They are also known as Arecuna/AricunaJaricuna, , Kamarakoto/Camaracoto, Taurepan/Taulipang.[1]

They are one of several closely related peoples called Ingarikó and Kapon, and sometimes go by the name of the Macushi (Macuxi, Makuxi).

Pemon (in Spanish: Pemón) is a Cariban language spoken mainly in Venezuela, specifically in the Gran Sabana region of Bolivar State. According to the 2001 census there were 15,094 Pemon speakers in Venezuela.

The Pemon were first encountered by westerners in the 18th century and encouraged to convert to Christianity.[3] Their society is based on trade and considered egalitarian and decentralized, and in Venezuela funding from petrodollars have helped fund community projects, and ecotourism opportunities are also being developed.[4] In Venezuela Pemon live in the Gran Sabana grassland plateau dotted with tabletop mountains where the Angel Falls, the world's highest waterfall, plunges from Auyantepui Canaima National Park.[5]

The Makuxi, who are also Pemon speakers, are found in Brazil and Guyana in areas close to the Venezuelan border.

The Pemon have a very rich mythic tradition which continues to this day, despite the conversion of many Pemon to Catholicism or Protestant religions spread by missionaries.

Pemon mythology includes gods residing in the grassland area's table-top mountains called tepui.[6] The mountains are off-limits to the living as they are also home to Ancestor spirits are called "mawari".[7]

The first non-native person to seriously study Pemon myths and language was the German ethnologist Theodor Koch-Grunberg, who visited Roraima in 1912.

Important myths describe the origins of the Sun and Moon, the creation of the tepui mountains, which dramatically rise from the savannahs of the Gran Sabana and the activities of the creator hero Makunaima and his brothers.

The Baniwa

The Baniwa language belongs to the Arawak linguistic family and is closely related to the language of the Bare, Tsase, Warekena, and the Wakuénai.

It is spoken by approximately two thousand people scattered throughout Venezuela, Colombia, and Brazil.

Like other ethnic groups of the Río Negro region, the Baniwa suffered greatly from exploitation by the rubber industry early this century.

Their numbers were diminished and their culture transformed.

Today the remaining Baniwa live in Maroa, capital of the department of Casiquiare in the Venezuelan state of Amazonas, and in Colombia, near the Caño Aquio and the Isana River.

The region’s history of violence also spurred migration toward San Fernando de Atabapo, San Carlos de Río Negro, Santa Rosa, Puerto Ayacucho and the Xié River in Brazil.

The progressive abandonment of their ancestral ways of life has made the Baniwa increasingly dependent on industrial products.

Today, many people buy even traditional foods like manioc and cassava from criollos, sometimes at very high prices.

Although market foods make up the bulk of the Baniwa diet, they do hunt, gather, and fish according to cycles of rain and drought.

However, since most Baniwa children attend criollo schools, it is often difficult to coordinate these collective activities with the school year calendar.

For hunting monkeys and birds like the toucan, the Baniwa make blowpipes as well as bows and arrows with bone arrowheads.

They also use bows and arrows to fish. As their traditions have disappeared, so has much of their material culture.

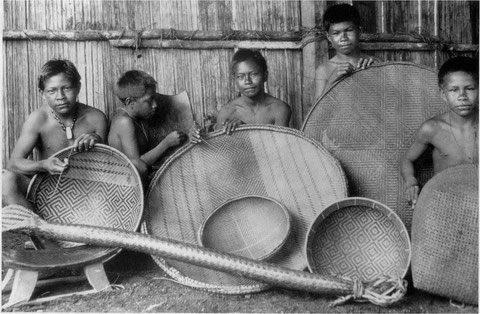

Although in the past they had been skilled in pottery and basket-making, with very few exceptions, these crafts have not been passed on to new generations.

The few families who still work in basketry make esteras, guapas, sebucanes, mapires, catumares, and sopladores, the ventilators used to stoke fires.

These crafts are made with the tirite, mamure, moriche, and cucurito fibers.

Chiquichique fibers are used to make the small brooms used to spread flour when making cassava.

Although they spin cotton, the Baniwa do not make their own hammocks, as they prefer to purchase ones made of cloth in Colombia.

Among the musical instruments still played are the yupurutú, whistles made with the stems of mabe palm and the walking sticks, which they use to keep the rhythm of the dance during the Dabacurí festival.

When hit against the ground, the sticks make a drum-like sound.

Acculturation and assimilation have not meant a complete loss of ancient mythology.Their Creator Nápiruli (Iñápirrikúli) is a deity also honored by other Arawak groups of Southern Venezuela and Colombia.

The Baniwa belief system has much in common with the Tsase, Warekena, Wakuénai, and Bare peoples. Like the Bare, the Baniwa attribute the humid and cold climactic changes in the southwest state of Amazonas to magical and religious forces.

The Áparo, short men who carry thunder and lightning over their backs, are responsible for the climate. The Áparo are Mawali, or malignant spirits.

They navigate the turbulent and dark waters of the Guainía and Río Negro in tiny curiaras unseen by human eyes, bringing rain, wind, and fog. They soar over rivers during the rainy season, and, if seen, knock over the humans’ curiaras, sinking the fishing tools to the bottom of the river. Despite the fear that the Áparo evoke, the Baniwa, nonetheless, venture out into the rivers, like their forebears, in search of sustenance.

References Oscar González Ñáñez, Orígenes del mundo según los baniva, Venezuela Misionera, Caracas, 1970.

Robin Michael Wright, History and Religion of the Baniwa Peoples of the Upper Rio Negro Valley, Michigan, 1981.